Seven EU member states are finally allowed to put €1.2 billion into a common cloud project. The goal is to curb dependence on large U.S. hyperscalers.

It took a while, but there it is: the plans of seven member states to make Europe’s cloud infrastructure more autonomous have finally been approved by the European Commission after a year and a half of doubt. Originally, EC chief of competition affairs Margrethe Vestager was said to have been unconvinced of the plans, but her replacement Didier Reynders has given the go-ahead.

The project is known as IPCEI Next Generation Cloud Infrastructure and Services, or IPCEI CIS for short. The goal is to eventually carve into the huge market share that AWS, Microsoft and Google have obtained within the European Union. As things stand, together they represent 72 percent of the entire cloud market in Europe.

The seven participants in the project are France, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Italy, Poland and Spain.

Catching up for Europe

Specifically, the plans are meant to create an open and interoperable ecosystem for data processing and a cloud and edge infrastructure developed with open-source software. A shared reference architecture will have to act as a blueprint so that all kinds of vendors can build their own cloud and edge systems for various use-cases. Specific industries such as healthcare, energy and shipping, for example, stand to benefit, the European Commission asserts.

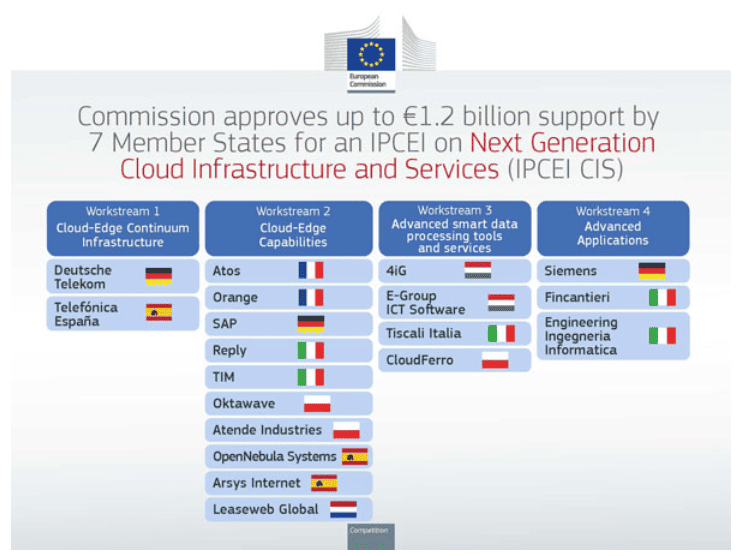

Nineteen projects have been approved, divided into four so-called “workstreams.” Parties such as Atos, Orange, SAP and Siemens are participating in things like “Cloud-Edge Capabilities” and “Advanced applications.” The list can be seen below.

The research, development and first practical application of the cloud project should all take place between 2023 and 2031. An ambitious timeline, especially considering that a previous project of a similar nature has been anything but successful.

The Gaia-X initiative, part 2?

That only seven countries and 19 companies are participating in IPCEI CIS is striking. It’s in stark contrast to Gaia-X, which now has 377 members. However, that project, designed to ensure European sovereignty over its data traffic, is now notorious due to how it has gone astray. Although some concessions have been made by tech companies to protect data sovereignty for the continent’s nations and organizations, Europe is far from self-reliant in this area.

In an analysis two years after Gaia-X was conceived, Politico blamed an overabundance of stakeholders and a lack of direction for the project’s failures, while analysts at Forrester Research point to the Covid-19 pandemic and too much bureaucratic red tape as culprits.

As far as IPCEI CIS is concerned, expectations will not be too high as a result of Gaia-X’s legacy. Nevertheless, the smaller scale of merely seven nations, 19 companies and four specific directions of interest offer hope. The first findings will not be presented until late 2027, so the jury’s out until then.

Also read: Europe divided: what will remain of the AI Act?