The European Union has global plans for undersea Internet cables. In 2024, it will present a new strategy to drive the continent’s telecom sector and Internet infrastructure. However, mutual competition and a lack of budget may throw a spanner in the works.

For several years, EU member states have had a stated ambition to improve Internet connectivity. In 2020, the European Commission concluded that the development of new infrastructure was necessary to be “digitally sovereign”. Strengthening Internet connectivity within the continent as well as between Europe and Africa, Asia and Latin America was specifically mentioned during Digital Day 2021.

99 percent of all intercontinental data traffic runs through undersea cables. Currently, EU lawmakers find the existing infrastructure too fragile and open to sabotage. An internal paper from the European Commission about the matter was seen by Politico. In it, EU officials say that a “secure undersea infrastructure for Europe” is going to be a non-binding recommendation to national governments. Current restrictions are supposedly too often a roadblock to projects. Such restrictions are to be alleviated by a Digital Networks Act in 2024. After that, more capital is supposed to be made available to realize more ambitious infrastructure plans.

Two rings

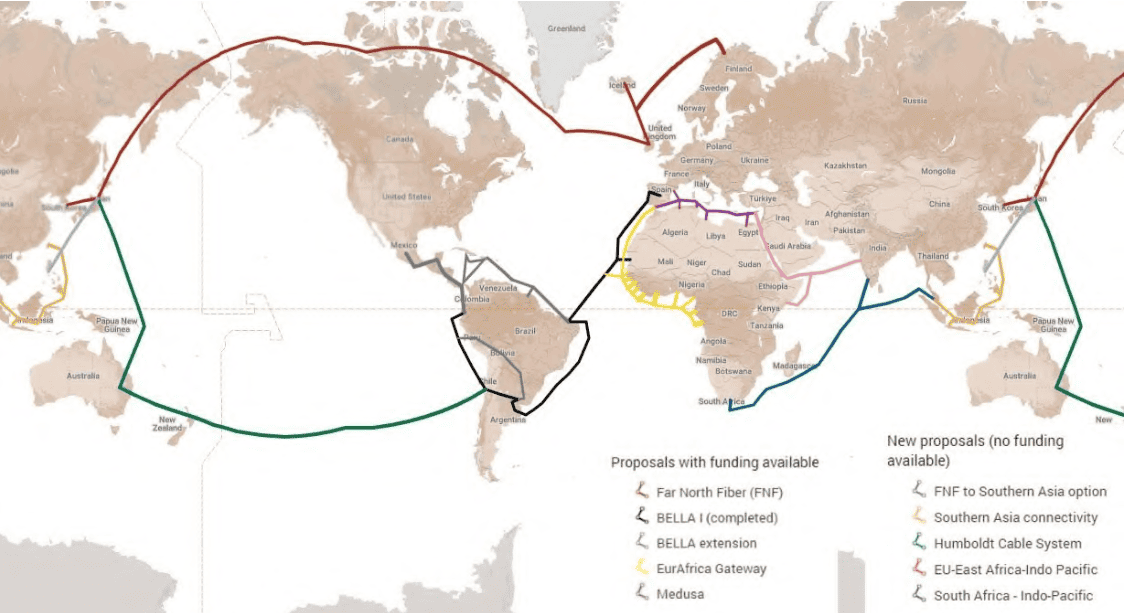

The EU is targeting two sets of infrastructure projects. Firstly, there’s a plan for a so-called “EuroRing” intended to support Internet traffic within Europe. In addition, a “Global Ring” should ensure that areas of great strategic importance are better connected to the continent.

These plans should finally lend some additional weight to the previously announced “Global Gateway Initiative.” That plan was formulated under Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in late 2021. If all the projects involved in that initiative were to take place, it wouldn’t just signal the arrival of high-quality connections between Europe and the rest of the world. The so-called Humboldt cable system, for example, isn’t even set to be built anywhere near the shores of Europe. It’s aim is to connect Japan with Australia and Chile, while the South Africa – Indo-Pacific cable would run between South Africa, India and Malaysia. As it happens, none of this is budgeted for: these are simply loose proposals that are subject to a great deal of change.

Within Europe itself, however, there are five plans that do have budgets available. These run exclusively to and from northern and southern Europe, with most of the money currently going toward projects connecting Africa to Europe. Partner countries get a say in exactly how the cables run. An anonymous EU official told EURACTIV that there is “no justification for the investments,” with an alleged unfair and non-transparent decision-making process at the core of discussions.

Companies interested, but mutual conflicts member states

Contracts to lay undersea cables can be hugely lucrative. There’s also much to gain for member states, which can develop certain areas into data hubs, something Amsterdam, Frankfurt, London, Paris and Dublin have succeeded in with previously laid Internet infrastructure. The speed, reliability and central location of these points makes them very attractive for building data centers.

Tip: Turnkey Internet opens European data center in Amsterdam

For these existing markets, the previous plans will not seem very attractive. Meanwhile, Portugal aims to position itself as a new critical hub for connectivity to Latin America and Africa. Before the plans are realized, member states that do not play a major role in the new projects will have to be convinced alongside current players that already have a well-established level of connectivity.

However, there is a fundamental common interest underlying these European plans: the desire to limit and, where possible, get rid of vulnerabilities. Just as the EU wants to guarantee its own sovereignty in the field of semiconductors through the European Chips Act, it also hopes to establish its independence from any other nation or entity when it comes to digital infrastructure. Just last weekend, a data cable (and a gas line) between Estonia and Finland was hit; its cause (or perpetrator) is still unknown. Elsewhere, the EU already has plans to build an Internet cable in the Black Sea, so Georgia is connected to Europe even without a cable through Russia.