US authorities could access the metadata of public cloud users, even if they use the sovereign offering of an American hyperscaler. According to a Dutch legal firm, the Americans cannot access customer data on the AWS European Sovereign Cloud, although the same cannot be said about all metadata. At what point does customer data become metadata? And what could one learn about cloud users based on the metadata they leave behind, even if their ‘personal’ data appears to be secure?

Metadata is always difficult to define. In fact, it is effectively infinite, because information about information can occur in any and all forms. It forms the basis for search engines and administrative processes. In addition, it is useful for monitoring IT systems. This is why hyperscalers, whether they are called AWS, Google Cloud, or Microsoft Azure, retain access to certain metadata. Examples of such data includes capacity management, system health, the number of deployments, and fraud detection systems. So-called operational metadata leaves Europe when it comes to AWS in any case, and presumably the same applies to Google and Microsoft. Even Microsoft’s EU Data Boundary does not rule out some metadata reaching America from Europe.

The hyperscalers all make slightly different distinctions between types of metadata. For example, Microsoft uses diagnostic data for when administrators or users work with a service, including IP addresses, client locations, and routing information. Service-generated data concerns traffic patterns and logs about usage for health monitoring. Google Cloud does roughly the same thing with Admin Activity and Data Access audit logs. At AWS, telemetry is discussed in the same way that the other two cloud giants talk about metadata. The company collects this data to “understand how features are used and to improve our services.” There are opt-outs for AI training and user behavior, but not for telemetry for packet routing and billing.

Valuable information

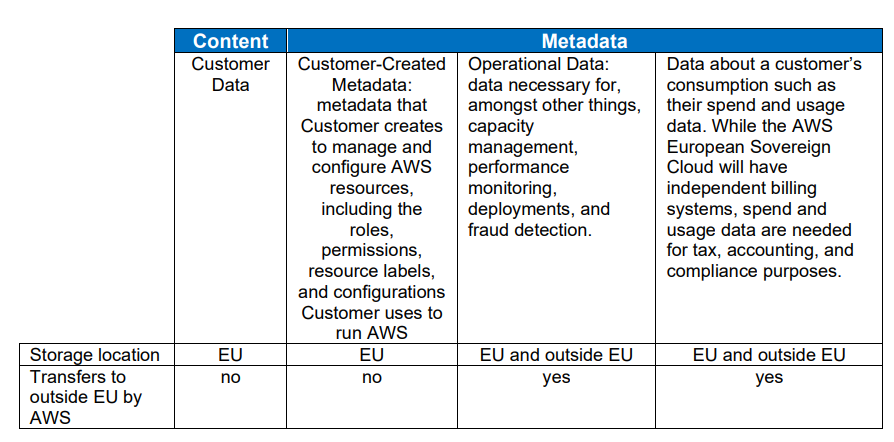

In the context of the public cloud, metadata is far from monolithic. The exact classification of purchased resources, roles, permissions, resource labels, and configurations belong to the customer data. AWS cannot access this, according to an analysis by law firm Greenberg Traurig on the Dutch applicability of AWS’ sovereign offering. Below is the report’s overview of the split metadata (we would link to it, were it not for the fact it was taken offline for some reason):

The division of metadata is understandable, but it does rely on the hyperscaler’s good behavior. The data that AWS has available from a foreign government agency that uses the European Sovereign Cloud is still considerable. At the very least, the metadata shows what an AWS customer consumes in terms of cloud resources and what they pay for them. Since the exact information is not shared by the hyperscalers, it is unknown whether that consumption can also be localized. The AWS European Sovereign Cloud is managed as a separate entity outside the regular AWS, so because of that separation, even anonymized data is less anonymous than you might think. There may be relatively few sovereign customers, and if AWS can determine which data center is being used and how many resources are being used, it may be easy to identify which customer is involved.

The problem with that conclusion is that we cannot know for sure. It is precisely this lack of clarity that makes metadata a ‘black box’ for sovereignty. It is also important for ordinary customers to pay attention to metadata. Since cloud players never reveal their architecture in detail, it remains a matter of guesswork. Hence the emphasis on who can view the metadata, beyond what that metadata actually is.

Who versus what

The implication behind splitting up metadata is that not all of this information is equally important to keep private. According to the hyperscalers, customer data ‘itself’, i.e. the actual files, applications, and identities of a cloud environment, remains within the European Union for sovereign customers. The metadata generated directly by the configuration of the customer’s own environment also remains within the EU.

The recent report by Greenberg Traurig points out that AWS Sovereign Cloud metadata is subject to an additional ‘layer of protection’: European employees. Eventually, it must be fully staffed by European citizens who also reside within the EU. This shows that the company is aware of the unclear nature of metadata; without knowing exactly what AWS knows about customers, it is important to confirm who gets to see this information.

Metadata is subjective by definition

In general, metadata exists because of an artificial separation. Those who monitor the functioning of a public cloud actually use the metadata discussed above as their primary information. Metadata may also be much more important to a vendor for the end user than for a platform administrator. Consider the data breach at X in April 2025, when, in addition to email addresses, location data and the app from which a user sent a message were also compromised. Such data can be used just as effectively for a convincing phishing email as ‘primary’ information such as private messages. The use of the term ‘metadata’ here is only useful to soften the emotional impact of a data breach.

Popular fitness apps also tend to view location data as ‘metadata’, even though users’ GPS routes are so sensitive that they can locate someone’s home or reveal the existence of secret military bases. This loose interpretation of metadata does not necessarily stem from malicious intent. For a software team, the primary data normally consists of account information, settings, (private) messages, bank details, and more sensitive data. However, context is everything, and users rarely know what their data can reveal about them beyond their own profile.

The fact that developers do not always recognize the danger of metadata is evident from the fact that Git commits regularly reveal user names , workstation names, or the IDE used. Leaving extra information lying around that does not immediately appear to be sensitive has become a habit.

Within the specific context of a sovereign cloud, metadata suddenly becomes a visible weak spot, precisely because it is unclear and deliberately disclosed incompletely. This lack of clarity gives a hyperscaler leeway to store, even in good faith, additional information that keeps its own infrastructure running. This creates a gray area in which information about information can be very revealing in itself. Everything depends on the context in which it is found, and if that context reveals enough, the metadata is valuable. For this reason, it is important to ask yourself whether you, as a cloud user, can make yourself completely anonymous, regardless of the possibility of a malicious party gaining access through social engineering. For now, it seems more important to know who is collecting this data and why than what exactly that data says, whether it is called private data or metadata.

Also read: Is the AWS European Sovereign Cloud sovereign enough?