Research from Splunk’s SURGe division shows that there are major differences between ransomware variants in how fast they operate. Why is that important for organizations to know? And what does that mean for Splunk’s product offering?

We talk about the above and other issues with Johan Bjerke, Principal Security Strategist at Splunk. SURGe is the company’s cybersecurity research arm and has been researching how different ransomware strands behave once activated. The main goal of this research was to learn more about how ransomware behaves. And especially how fast it works. After all, that’s very important in determining what you can do about it.

The general idea behind the research is that you can take better action against something if you have a better understanding of what it does and how it works. So in part it’s an academic exercise, not necessarily a study of what you should do as an organization against ransomware. A few weeks ago we already published a short news item about this research. You can read that here. In this article, we’ll go a little deeper into this based on our conversation with Bjerke.

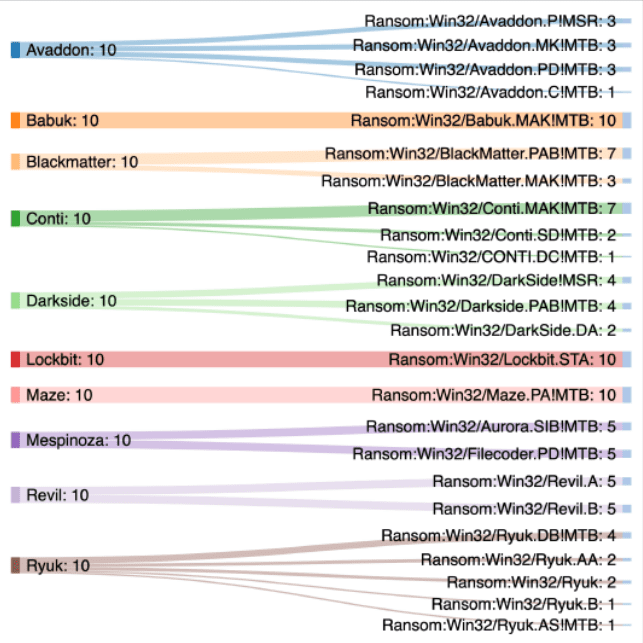

Before we continue, below is the list of types of ransomware that Splunk SURGe investigated by having the ransomware encrypt just under 100,000 files in Windows 10 and Windows Server 2019 environments. For both environments, they tested systems or instances with very powerful configurations, but also with less powerful specs.

Big differences in ransomware…

When we ask Bjerke what he was most surprised about when researching the ten different strains of ransomware, he gives a clear answer. “Not all ransomware is the same, there are huge differences,” he indicates. This is visible in several areas. The first is that there are differences in how easy it is to activate the ransomware. For example, one of the ten variants (Babuk) could not be activated remotely via a PowerShell script. The research team also found considerable differences in terms of hardware support. Some strains could handle HyperThreading better, for example.

In addition, some strains of ransomware are a lot more mature than others. As an example Bjerke mentions the LockBit variant, which you purchase via a Ransomware-as-a-Service construction. That is, cybercriminals are also going with the trend of offering everything as a service. In fact, the people behind LockBit are doing some proper marketing. They even have research report on their (dark web) page, in which they indicate that LockBit is the fastest of all.

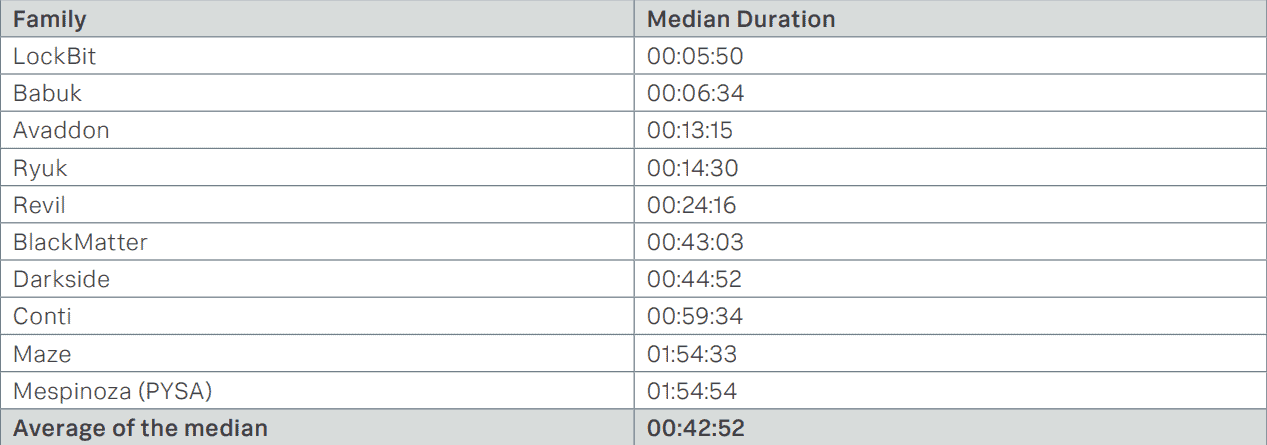

However, the biggest differences between the different ransomware strains that SURGe found during the research was about the speed at which they could encrypt files. The differences were very large in this regard. Below you can see a list the medians of performance when encrypting just under 100,000 files on the different instances with the different specifications.

…are not hugely relevant in practice

The differences between ransomware families are interesting from a theoretical point of view. After all, they indicate that there is a lot of variation in ransomware. However, it also made us wonder what this means in practice. As it turns out, it doesn’t really matter for organizations which ransomware hits you. Bjerke mentions that the median time it takes to find out that something is wrong is three days. On such a timescale, it doesn’t make much difference whether encrypting your files takes six minutes or two hours. “When you see ransomware at work, there’s already nothing you can do about it,” Bjerke sums it up.

From the perspective of practical applicability of the research conducted by Splunk SURGe, it doesn’t directly add a lot of value for organizations. It makes no difference at all which variant you are attacked with, you are always too late if you only start doing something when ransomware strikes. That in itself is nothing new; many victims of ransomware can undoubtedly testify to this.

However, studies such as this one are certainly relevant from a different perspective. They once again demonstrate that ransomware needs to be caught as early as possible. As the SURGe researchers put it in their report: “If an organization wishes to defend against ransomware, it’s clear that they need to move left on the cyber kill chain.”

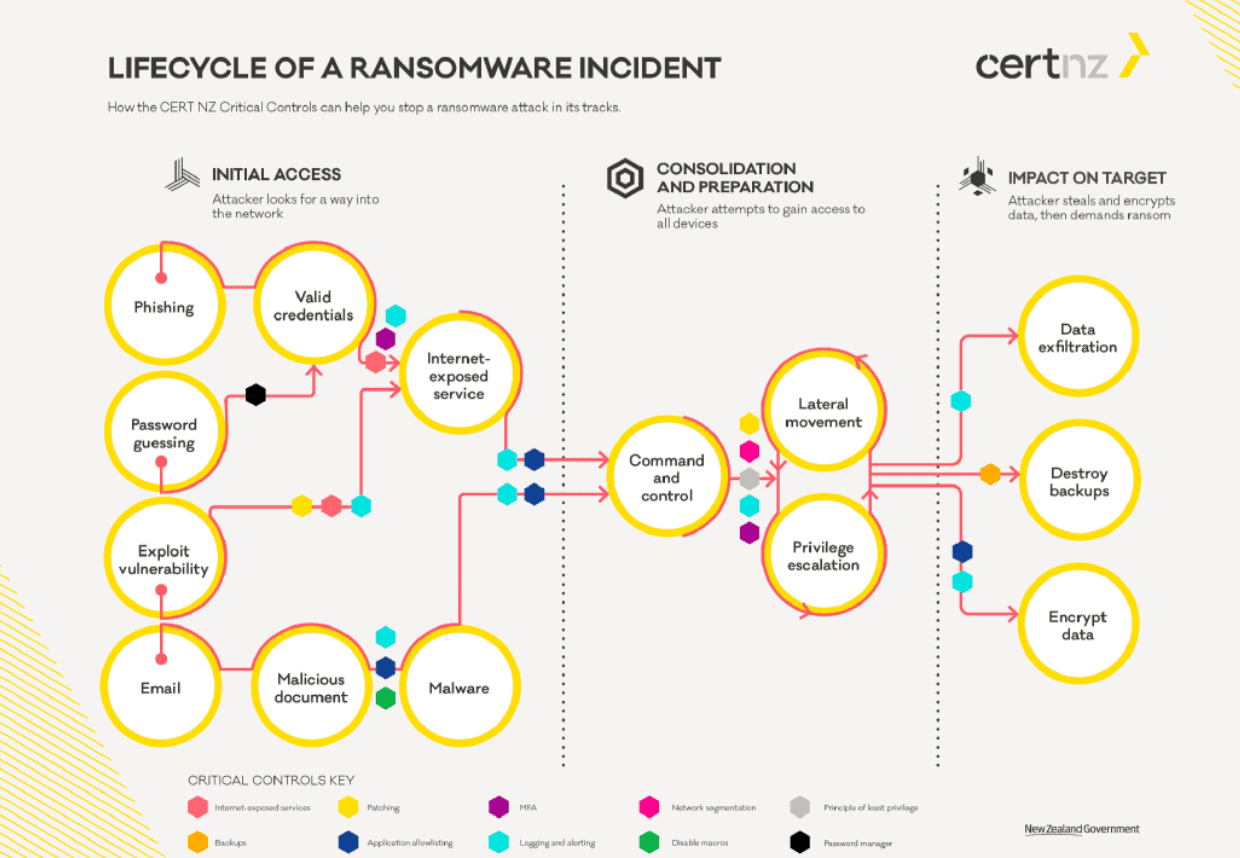

Ransomware is an APT

The above quote from the researchers can be interpreted in several ways. First of all, you can conclude from it that organizations would do well to shift their investments somewhat more towards prevention. However, you should not be blinded by this, according to Bjerke. “Prevention is great if it works, but you certainly shouldn’t have a 100 percent prevention strategy when it comes to ransomware,” he states. It should be about defense in depth. Specifically, you need to make sure that there are at least four, five layers between ransomware entry and the encryption stage.

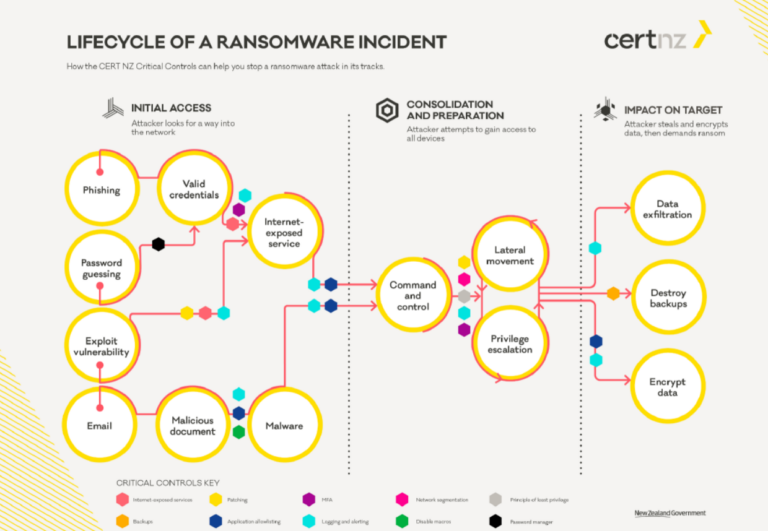

Ultimately, it must become clear to organizations that ransomware is not just about the encryption stage. To achieve this, it is important to treat ransomware as an Advanced Persistent Threat (APT). That is, you need to understand the entire lifecycle of ransomware and design your investments and cybersecurity training accordingly. Downloading the ransomware binaries is the last thing a ransomware attack does. Before that, there has already been the infiltration itself, which can also take place in a variety of ways. In addition, a ransomware attack can also move laterally within your organization, for example.

In order to more effectively deal with ransomware, you shouldn’t treat ransomware as ransomware alone. That is, you shouldn’t try to detect ransomware, but rather the ways in which it gets in. “It’s mainly about getting your basic security in order, through timely updating, patching,” Bjerke summarizes. In other words, it’s mainly about sticking to best practices.

Future for ransomware and the research

If an organization adheres to the best practices in terms of cybersecurity, it is already taking significant strides towards significantly better protection. However, the chances that we will no longer need to talk about issues such as patching, and thus indirectly about ransomware, in the future, are very slim, Bjerke says. Patching will become an increasingly smaller issue, though. That has to do with the transition to the cloud. This transition means organizations will largely outsource patching to the providers of the cloud platforms and SaaS tools. However, legacy systems will still be around for decades to come. These will undoubtedly remain the preferred entry points for cybercriminals.

When it comes to ransomware research, Splunk SURGe has several plans to extend and elaborate on this first piece of research. First of all, in a subsequent study it wants to examine whether it can also detect unknown ransomware families. In other words, it is going to investigate whether it is possible to detect unknown ransomware based on its behavior. In addition, the intention is to make all 200 GB of data from the current research available on bots.splunk.com. The purpose of this is to enable anyone who wants to work with it to do so and extract valuable insights from the data.

Integration into Splunk offering

A little further in the future, Splunk also wants to be able to offer clear tools to organizations based on the results of its own research. Bjerke describes this as creating an interactive manual for organizations to optimally defend themselves against ransomware. Since Splunk is not a pure play cybersecurity company, it has different discussions with customers compared to players who only do security. That gives Splunk the opportunity to also reach other parts of the organization more easily. If you treat ransomware as an APT, that’s more or less required anyway, because its lifecycle involves the entire organization.

If you’d like to know more about the research we’re discussing in this article, the white paper SURGe wrote about the research can be downloaded via this link. All images in this article are from that whitepaper.