With “Operation PhishOFF,” phishing gang LabHost appears to have exited the cybercrime stage. This criminal group was broken up through international cooperation between 18 countries and security services. But how did the LabHost members operate? And how did they eventually get caught?

LabHost was founded in 2021 and made it possible to create phishing websites with just a few clicks. The user base of more than 2,000 could choose from fake versions of legitimate websites or request new bespoke scam sites to be built. As is often the case, these pages mostly mimicked banks, health care agencies and postal services to extract sensitive data from victims.

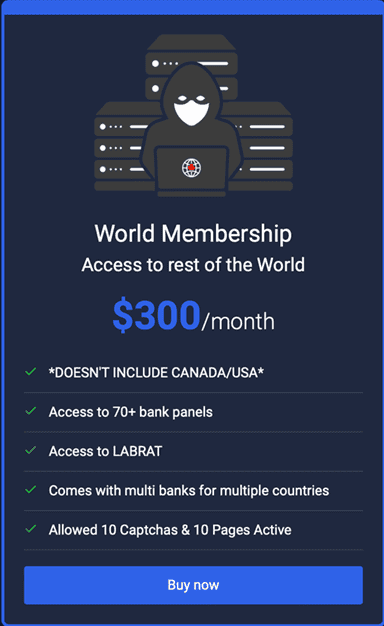

These 2,000+ users paid a monthly subscription to access the service, earning LabHost about 1.1 million euros. The highest-tier “worldwide membership” cost between 230 and 350 euros per month, which threat actors could make use of by setting up phishing campaigns on an international level. The LabHost group created more than 40,000 fraudulent sites in just three years.

Infiltrated and unmasked

The run-up to LabHost’s demise began as early as mid-2022. In June, British authorities received a tip-off from the Cyber Defense Alliance (CDA), a nonprofit set up by four international banks. Once the scale of LabHost’s operations became clear, British police called in other units. In addition to local organizations, Europol and other national authorities became involved. Private partners such as Intel471, Microsoft and Trend Micro also played a crucial role.

The British authorities managed to infiltrate LabHost and were then able to identify suspects within this criminal circuit. The platform was interrupted, after which authorities informed 800 users that they had been exposed. This was done by converting regular LabHost messages into a police notification. Members were shown details about how much they had paid LabHost, what other sites they had visited and how much data had been shared with them. In other words, it was a clear message to let criminals know they’d been had and couldn’t simply continue their work. “In the coming weeks and months”, these former LabHost users could expect another knock on the door, British police have rather ominously stated.

Outsourcing

LabHost’s example of a modern digital criminal enterprise is one of many. Phishing is the most commonly used form of deception for cybercrime purposes by far. Meanwhile, threat actors nowadays specialize in a particular branch of the cybercriminal ecosystem. Multiple parties provide services to others in return for payment, such as Phishing-as-a-Service in the case of LabHost, in addition to, for example, Ransomware-as-a-Service (see LockBit) or Malware-as-a-Service (such as ZeuS).

Initial access brokers (IABs) like the defunct Genesis Market make it easy for other criminals to find their victims. After a transaction, malicious actors have enough data to compromise a target, such as personal details that enable credible, personally targeted e-mail messages.

A Europol report concluded in September that this commodification and specialization in cybercrime leads to faster, more approachable attack campaigns. It also leads to professionalization. LabHost’s interface, for example, was indistinguishable from a legitimate service.

Assistance: example Trend Micro

Trend Micro, one of the parties involved in Operation PhishOFF, shares via a blog how it helped take down LabHost. Specifically, the company investigated, among other things, the infrastructure deployed by the criminal service and the phishing pages connected to users. In addition, Trend Micro performed triage and clustering to track down LabHost users, then examined specific key individuals in great detail.

The investigation also revealed what the attack patterns of LabHost members looked like. One example shows a “smishing” attack in which the malicious person poses to the victim as the Irish Tax and Customs service via an SMS. The message states that tax must be transferred before a delivery can occur. The attacker then guides the victim to a full-fledged payment service that obtains credit card information. The domain “custom-express.info” does not seem too suspicious at first glance, while the website’s interface is indistinguishable from the real thing.

Trend Micro reports that this example also plays into the expectations of Irish users in particular. After all, citizens in this country have to deal with customs service messages relatively often since deliveries regularly go through the United Kingdom or the United States. In other countries, attackers choose somewhat different tactics appropriate to the country in question.

Also read: Ransomware pauses beer production at Duvel, La Chouffe and Liefmans -update

Fed up?

The question now is whether LabHost is gone for good. Authorities and Trend Micro indicate that the group has been infiltrated extensively, making the entire network appear like it has been effectively destroyed. In addition, the police now know a variety of the individuals involved —more arrests may follow.

Victims have now been notified, at least within the United Kingdom. British police have recognized 70,000 victims on their own territory and contacted 25,000 of them. Worldwide, LabHost managed to obtain 480,000 card numbers, 64,000 PIN numbers and more than a million passwords.

As usual, the advice from those involved in the operation is to create greater awareness around phishing. It is essential to create a working environment where people who fall for phishing feel free to report it. For individual victims, the actual reporting of such cybercrime is also crucial, although unfortunately, this is still too often neglected.