Tracking cookies have been a hot topic for debate for years. Ever since advertising companies first used them to build up a profile of Internet users, privacy activists have been calling for something to be done about it. Most browsers now block these cookies by default, but the largest of all, Google Chrome, does not yet do this. Google does intend to do so eventually but first wants to have its own alternative ready.

The consideration of the use of tracking cookies is tricky. On the one hand, many websites rely heavily on advertising revenue to keep their heads above water. However, it is a huge task to do all kinds of marketing deals yourself, so many companies choose to work with an external advertising provider.

On the other hand, consumers and privacy activists complain that their behaviour on the Internet is closely monitored, so that very detailed profiles of the interests and habits of almost every Internet user in the world now exist. There have already been several attempts to do something about tracking cookies by law. The Netherlands was one of the first countries to do so when it added article 11.7a to the Telecommunications Act in 2012. This article was also known as the cookie law. According to this legislation, websites must ask visitors for permission to place non-functional cookies on websites. Since the introduction of the GDPR in 2018, such policies have been in place across the European Union.

However, the cookie laws have led to annoyances from users, who were confronted with a pop-up on every website asking to accept cookies. Many users just click the big ‘accept all’ button out of convenience, especially since many websites make it very difficult to choose specific options. In many cases, this negated the usefulness of the cookie laws.

Tracking cookies blocked by more and more browsers

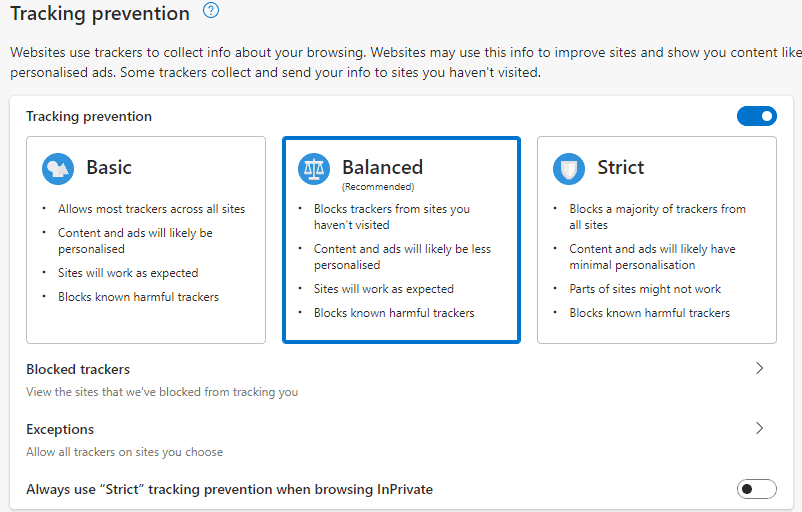

Meanwhile, more and more browsers are taking matters into their own hands. In September 2019, Mozilla announced that it would start automatically blocking tracking cookies in both the desktop and Android versions of its Firefox browser. Apple followed suit six months later: since May 2020, third-party cookies are blocked by default in Safari. In Microsoft Edge, users can choose from various degrees of blocking tracking cookies in a simple overview. By default, the browser is set to ‘balanced’, which blocks trackers from new websites.

A notable exception in this case is Google Chrome. Chrome is by far the most popular browser in the world, holding more than 60 percent of the market. Chrome still accepts tracking cookies by default. Google has already announced that it wants to do this eventually, but is in no hurry to do so. The reason why Google is lagging behind its competitors is obvious: Mozilla markets itself as a company that values privacy and openness and implements this policy in its open-source browser Firefox. Apple also likes to sound like a privacy advocate. Microsoft is desperately trying to gain market share with Edge and seizes every opportunity to put itself in the positive spotlight.

However, Google has a completely different view on this issue. The company is fundamentally an advertising company and, since its acquisition of DoubleClick in 2008, has held the world’s largest advertising platform with Google Ads. If Google were to block tracking cookies, the company would be shooting itself in the foot. Mozilla, Apple and Microsoft, however, get their revenue from elsewhere.

Google invents alternative for cookies

Before Google abandons tracking cookies in its Chrome browser, the company first wants to be completely sure that it can still generate income from targeted advertising in another way. That is why earlier this year, the company announced an AI system to replace its tracking cookies, called Federated Learning of Cohorts (FLoC).

The AI works like this: the browser itself makes a user profile based on the user’s browsing behaviour and stores this profile locally on the computer. When the user then goes to a website that wants to serve advertisements, the user’s computer sends an identification number to the website. The identification number gives advertisers a general idea of the user’s interests but not a detailed overview of previous movements on the Internet. Google intends these identification numbers not to become unique; thousands of users would receive the same number. This means that the advertisements are somewhat less focused on the specific user, but according to Google, they are still 95 percent as relevant as when tracking cookies would be used.

Google is building a monopoly

In theory, this product would indeed provide much improved privacy compared to the use of tracking cookies. However, this development also creates a stronger monopoly position for Google in the field of online advertisements. After all, if a website wants to be able to place personalised advertisements via an third party, then it can only turn to Google for its advertising services. Other advertising services that still use cookies are then blocked by almost all browsers. This means that it is no longer worthwhile for websites to do business with advertising providers other than Google.

Whether Google’s FLoC catches on or not, it will certainly be interesting to see to what extent it will be supported by other browsers. The way the system is currently set up, it sounds like it’s all about Google: Google’s browser only shows personalised ads from Google’s advertising platform. Conversely, the ads from Google’s advertising platform are only shown in Google’s browser. After all, it is not likely that Mozilla, Apple and Microsoft will incorporate the system into their browsers.

Alternatives for Google’s system

Are there no other alternatives for tracking cookies? Yes, there are. Microsoft is working on a system that the company calls Parakeet. With this technology, personal data is first anonymised before it is sent to existing advertising networks. However, this project is still in an early stage of development.

Advertising company The Trade Desk is also working on its own alternative. This alternative, called Unified ID 2.0, works based on users’ e-mail addresses. When users log in to a website, an encrypted version of their e-mail address is sent to the advertisers. The email address is salted and hashed so that the advertisers cannot trace what the email address actually is. Users can indicate exactly what interests them and what kind of advertisements they want to see.

The initiative is supported by a large number of advertising providers, such as Index Exchange, Magnite, PubMatic, OpenX, SpotX, Criteo, LiveRamp and Neustar. A number of publishers have also already announced their collaboration. Eventually, Unified ID 2.0 will come under the management of an independent company.

Neither of those systems sounds perfect, though. The data stored in Parakeet and Unified ID 2.0 may be directly traceable to a specific user, but there is still a unique user whose browsing behaviour is tracked. With some effort, it might still be possible to trace this back to a specific user. In this sense, Google’s system offers more privacy. However, do not forget that many users synchronise their entire browsing history with Google and that we have to assume that Google cannot access this data.

The future of personalized ads is at a turning point

We are at the beginning of a major shift in the way websites serve ads to their users. Google’s proposal seems most likely to succeed, purely because Google controls both the largest browser and the largest advertising platform. However, this does seem to give Google a monopoly on online advertising. Regulators will likely intervene in that case. The plans of Microsoft and The Trade Desk are also still in their infancy. Websites will probably eventually opt for a mix of these providers.

Perhaps the era of personalised ads based on browsing behaviour will come to an end, and advertisers will fall back on ads relevant to the website they are placed on. It is also likely that more websites that used to offer free content will feel compelled to look for other sources of income. End users themselves may also have to reach for their wallets a little more often.